AIRCRAFT LOGBOOKS

Aircraft logbooks are one of the most misunderstood aspects of business aircraft operation. Why is that you ask? Well, for starters, looking through the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARS) to determine what we should put into an aircraft logbook does not help us very much. For the professional aviation maintenance technician, this lack of understanding of what needs to be included in a logbook, and what a proper and well-documented logbook should look like are often the source of hours of frustration and wasted time trying to find important information in the aircraft’s record.

For the aircraft owner, this wasted time equates directly to money, time the aircraft spends on the ground instead of flying, and can even mean the safety of the aircraft itself. For aircraft owners and maintenance people alike, what’s in (or not in) an aircraft’s record will have major consequences when it comes time to having work accomplished on the aircraft or to comply with an inspection and/or a Return to Service.

The FARS were written, as most government regulations are, in such precise detail that it’s hard to understand, from a “big picture” viewpoint, what a quality aircraft logbook should look like. Using the FARs for understanding logbook administration typically results in, to use a common catchphrase, “not being able to see the forest for the trees”.

This is most unfortunate. Because an aircraft’s logbook is one of the most important assets an aircraft has. A logbook is meant to give us a history of the aircraft and proof that the aircraft is Airworthy. Since the reality is that an unairworthy aircraft is nothing more than a huge ramp weight with wings, it stands to reason that if the aircraft’s airworthiness cannot be proved, it becomes useless as a flying machine. That’s why the commonly accepted norm for the value of an aircraft’s logbook is that it’s worth 30% or more of the total value of the aircraft.

So, what exactly needs to be in a logbook to prove the aircraft’s airworthiness? That is a question aircraft maintenance technicians wrestle with every day. Because of a lack of simple instructions from the FAA concerning the proper administration and overall content of an aircraft’s logbook, we find logbooks in every conceivable format, administered differently by every individual flight operation, and either lacking the data necessary to prove the aircraft’s airworthiness or containing so much unnecessary data, that it becomes almost impossible to separate the “wheat” from the “chaff”.

THE SIMPLE TO THE COMPLEX

Even though the minimum amount of information necessary to have in the aircraft record is stipulated in the FARs, the exact type of information is not understood by most technicians for reasons cited previously. Consequently, maintenance personnel often collect every piece of paper generated over the lifetime of the airplane and include it in the logbook. This, of course, results in a tremendous amount of data. But it also does one thing: it assures those who do not understand what is required to be in the logbook to be reasonably certain that at least the information that’s really-important is somewhere in the record. No matter how much confusion it creates.

Aircraft records can be simple; only containing the minimum amount of documentation to prove the aircraft’s airworthiness; or complex, having every bit of information that could one day be utilized by maintenance or operations to keep the aircraft flying. But no matter what style the logbook is, the objective should always be to have it organized so that someone/anyone can find the information the FARs say is necessary for it to contain.

One of the major events that the typical business aircraft’s record will go through occurs during the sale of the aircraft. Expensive business aircraft typically undergo a Pre-purchase Inspection to demonstrate to the potential buyer that the aircraft is airworthy and in the condition they expect, given the asking price of the aircraft and the market value.

It is at this time that the potential buyer will hire an experienced maintenance technician familiar with the make and model of the aircraft, and knowledgeable about what is required to be in the record, to investigate the aircraft’s airworthiness.

It’s a commonly accepted principle that the aircraft’s logbook will have been proven to have at least the minimum information required by the FARs after the pre-purchase inspection is complete, and that a “baseline” of compliance has been established on the aircraft.

So, what information is required to be in a properly documented logbook? I offer the following synopsis of the information we find in the FARs, with less detail so as to better understand what is required … using a “40,000 ft view” if you will.

To begin with, FAR Part 91.405 tells us that the aircraft owner is ultimately responsible for ensuring that the aircraft’s maintenance is accomplished and recorded in compliance with the FARs. This, of course, forms the basis for the following items that constitute the body of this requirement. And it is what you, as a maintenance technician, should certainly understand to be able to assure the aircraft owner that he or she is in compliance with this FAR.

According to FARs 91.411, 413, and 417, all aircraft records must contain the following information:

- A record of the maintenance, modifications, and alterations accomplished to the aircraft.

- The Total Time and Landings/Cycles on the aircraft and engines.

- The current status of all Life Limited and Calendar Overall components installed.

- The aircraft’s current Inspection Status.

- A comprehensive list of Form 337’s applicable to the aircraft.

- A list of ADs accomplished on the aircraft over its lifetime.

- The status of FAR Part 91.411 and 91.413 Altimeter and Transponder checks.

This, of course, is just a quick overview of the requirements. In order to really prove that each one of these items is in-compliance; a deeper dive into the aircraft’s records is required. This is where the experienced maintenance technician comes in. It’s important to understand each aircraft model’s unique requirements and the critical areas that must be addressed with respect to each item.

In order to better understand what this “deeper dive” entails, I offer the following dissertation on each of these. Again, this is not meant to be an exhaustive explanation of each point, but only to serve as a simple overview:

1. A record of the maintenance, modifications, and alterations accomplished on the aircraft.

The information necessary to include in recording each of these events is outlined in FAR Part 91.417(a)(1). In addition to the on-going maintenance events and Return to Service documents (FAR 43.9 and FAR 43.11), most logbook auditors are going to want to see a continuous and cohesive history of work on the aircraft. Gaps in the record, and/or periods of time missing, are suspect as to what occurred to the aircraft during that time period … even if the current status of the aircraft is proven Airworthy.

2. The Total Time and Landings/Cycles on the aircraft and engines.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(i) requires that the logbook contain a record of total time in service. However, this often becomes a “gotcha” moment for anyone auditing the logbook. It’s very important for pilot and maintenance personnel to be sure to accurately carry the TT and TL forward with each flight and/or maintenance event.

3. The current status of all Life Limited and Calendar Overall components installed.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(ii and iii) require a current status of the time-sensitive components to be kept in the record. But, for some reason, this seems to often be the biggest tripping point of the aircraft’s logbooks. The typical means to prove a component was “authorized” to install on the aircraft in the first place is an 8130-3 Airworthiness Tag. But for Life Limited and Calendar Overhaul components, it is the logbook that will indicate how much time was on the unit when it was installed on the aircraft. Although it’s important to keep a record of each time a component was replaced on the aircraft, only the time-sensitive components need to be tracked. Simple math then determines how much time we have left on each component.

Consider the following scenario as an example of a common problem with the aircraft record: An aircraft is undergoing a Pre-purchase Inspection to determine if the aircraft meets the criteria of airworthy.

In going over the time-controlled items, the buyer discovers a part had been changed on the aircraft. Since this part is a time-controlled item, they want to see the paperwork stipulating how much time was on the unit when it was changed. The seller points them to the maintenance tracking program. They think this satisfies the requirement. But, is this sufficient?

Absolutely not! Don’t make the mistake of thinking that just because you recorded the time/cycles on the unit in your Maintenance Tracking Program, you can prove the total time on the component. The FAA has gone on record that Maintenance Tracking is only a reference and cannot be used to prove any event. The easiest way to prove the time on any time-sensitive component is to keep the original 8130 that was received with the unit … and keep it in the logbook.

Without the 8130, or another way to verify the time on the unit when installed, the buyer will usually insist that the part be changed before buying the aircraft.

4. The aircraft’s current Inspection Status.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(iv) requires the record to contain a current inspection status. Whether the aircraft follows the OEM’s Recommended Maintenance Program or has its own, the time interval and type of inspections required are spelled out in the program. It’s a simple exercise to see that the aircraft is not only current with the latest inspection, but that all inspections have been complied with.

5. A list of ADs accomplished on the aircraft over its lifetime.

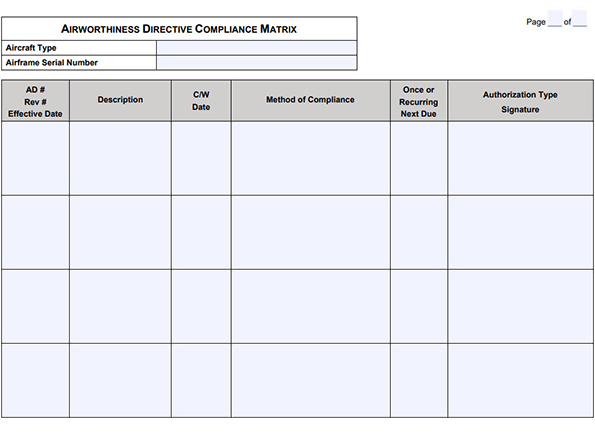

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(v) requires the current status of all applicable ADs. Although it is required for everyone to keep a record of the ADs accomplished on the aircraft, an AD Matrix (pictured below) is not required for aircraft operated under Part 91.

However, it’s always a good idea to keep a quick reference matrix on the aircraft. This list should include all ADs potentially applicable to the aircraft and component parts, with the ADs that are not applicable denoted as such. In this way, anyone doing a check of all possible AD Notes against the aircraft have already been addressed. Should the aircraft ever be placed on a 125 or 135 Certificate, an AD Matrix will most likely be required anyway.

Download this AD Compliance Matrix

6. A comprehensive list of Form 337’s applicable to the aircraft.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(vi) addresses the need to have a list of the current major repairs or alterations to the aircraft. This has become one of the most popular “plan B” alternatives used in any aircraft pre-buy. Since the FAA requires everyone completing a 337 on an aircraft to send a copy to the FAA in OK City, these “copies” of the 337s are almost always requested as part of the pre-buy. This does not, however, alleviate the owner’s responsibility to keep a copy of all the 337 modifications or alterations accomplished on their aircraft.

7. The status of FAR Part 91.411 and 91.413 Altimeter and Transponder checks.

FAR 91.411(a) and 91.413(a) address the aircraft’s altimeter and transponder system accordingly. The altimeter and transponders need to be checked every 24 months at a minimum. Every time these systems are checked it should be recorded in the logbook with a Return to Service entry.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Whether you’re a Pre-buy “expert” or just one of the many thousands of aircraft maintenance professionals working to keep business aviation flying; we should all know what’s required to be in an aircraft logbook.

As an aircraft maintenance professional, it’s your job to understand what is required to be included in an aircraft logbook, and how this information can be properly organized.

Knowing this information should come with the territory. It’s that simple.

AIRCRAFT LOGBOOKS

Aircraft logbooks are one of the most misunderstood aspects of business aircraft operation. Why is that you ask? Well, for starters, looking through the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARS) to determine what we should put into an aircraft logbook does not help us very much. For the professional aviation maintenance technician, this lack of understanding of what needs to be included in a logbook, and what a proper and well-documented logbook should look like are often the source of hours of frustration and wasted time trying to find important information in the aircraft’s record.

For the aircraft owner, this wasted time equates directly to money, time the aircraft spends on the ground instead of flying, and can even mean the safety of the aircraft itself. For aircraft owners and maintenance people alike, what’s in (or not in) an aircraft’s record will have major consequences when it comes time to having work accomplished on the aircraft or to comply with an inspection and/or a Return to Service.

The FARS were written, as most government regulations are, in such precise detail that it’s hard to understand, from a “big picture” viewpoint, what a quality aircraft logbook should look like. Using the FARs for understanding logbook administration typically results in, to use a common catchphrase, “not being able to see the forest for the trees”.

This is most unfortunate. Because an aircraft’s logbook is one of the most important assets an aircraft has. A logbook is meant to give us a history of the aircraft and proof that the aircraft is Airworthy. Since the reality is that an unairworthy aircraft is nothing more than a huge ramp weight with wings, it stands to reason that if the aircraft’s airworthiness cannot be proved, it becomes useless as a flying machine. That’s why the commonly accepted norm for the value of an aircraft’s logbook is that it’s worth 30% or more of the total value of the aircraft.

So, what exactly needs to be in a logbook to prove the aircraft’s airworthiness? That is a question aircraft maintenance technicians wrestle with every day. Because of a lack of simple instructions from the FAA concerning the proper administration and overall content of an aircraft’s logbook, we find logbooks in every conceivable format, administered differently by every individual flight operation, and either lacking the data necessary to prove the aircraft’s airworthiness or containing so much unnecessary data, that it becomes almost impossible to separate the “wheat” from the “chaff”.

THE SIMPLE TO THE COMPLEX

Even though the minimum amount of information necessary to have in the aircraft record is stipulated in the FARs, the exact type of information is not understood by most technicians for reasons cited previously. Consequently, maintenance personnel often collect every piece of paper generated over the lifetime of the airplane and include it in the logbook. This, of course, results in a tremendous amount of data. But it also does one thing: it assures those who do not understand what is required to be in the logbook to be reasonably certain that at least the information that’s really-important is somewhere in the record. No matter how much confusion it creates.

Aircraft records can be simple; only containing the minimum amount of documentation to prove the aircraft’s airworthiness; or complex, having every bit of information that could one day be utilized by maintenance or operations to keep the aircraft flying. But no matter what style the logbook is, the objective should always be to have it organized so that someone/anyone can find the information the FARs say is necessary for it to contain.

One of the major events that the typical business aircraft’s record will go through occurs during the sale of the aircraft. Expensive business aircraft typically undergo a Pre-purchase Inspection to demonstrate to the potential buyer that the aircraft is airworthy and in the condition they expect, given the asking price of the aircraft and the market value.

It is at this time that the potential buyer will hire an experienced maintenance technician familiar with the make and model of the aircraft, and knowledgeable about what is required to be in the record, to investigate the aircraft’s airworthiness.

It’s a commonly accepted principle that the aircraft’s logbook will have been proven to have at least the minimum information required by the FARs after the pre-purchase inspection is complete, and that a “baseline” of compliance has been established on the aircraft.

So, what information is required to be in a properly documented logbook? I offer the following synopsis of the information we find in the FARs, with less detail so as to better understand what is required … using a “40,000 ft view” if you will.

To begin with, FAR Part 91.405 tells us that the aircraft owner is ultimately responsible for ensuring that the aircraft’s maintenance is accomplished and recorded in compliance with the FARs. This, of course, forms the basis for the following items that constitute the body of this requirement. And it is what you, as a maintenance technician, should certainly understand to be able to assure the aircraft owner that he or she is in compliance with this FAR.

According to FARs 91.411, 413, and 417, all aircraft records must contain the following information:

This, of course, is just a quick overview of the requirements. In order to really prove that each one of these items is in-compliance; a deeper dive into the aircraft’s records is required. This is where the experienced maintenance technician comes in. It’s important to understand each aircraft model’s unique requirements and the critical areas that must be addressed with respect to each item.

In order to better understand what this “deeper dive” entails, I offer the following dissertation on each of these. Again, this is not meant to be an exhaustive explanation of each point, but only to serve as a simple overview:

1. A record of the maintenance, modifications, and alterations accomplished on the aircraft.

The information necessary to include in recording each of these events is outlined in FAR Part 91.417(a)(1). In addition to the on-going maintenance events and Return to Service documents (FAR 43.9 and FAR 43.11), most logbook auditors are going to want to see a continuous and cohesive history of work on the aircraft. Gaps in the record, and/or periods of time missing, are suspect as to what occurred to the aircraft during that time period … even if the current status of the aircraft is proven Airworthy.

2. The Total Time and Landings/Cycles on the aircraft and engines.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(i) requires that the logbook contain a record of total time in service. However, this often becomes a “gotcha” moment for anyone auditing the logbook. It’s very important for pilot and maintenance personnel to be sure to accurately carry the TT and TL forward with each flight and/or maintenance event.

3. The current status of all Life Limited and Calendar Overall components installed.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(ii and iii) require a current status of the time-sensitive components to be kept in the record. But, for some reason, this seems to often be the biggest tripping point of the aircraft’s logbooks. The typical means to prove a component was “authorized” to install on the aircraft in the first place is an 8130-3 Airworthiness Tag. But for Life Limited and Calendar Overhaul components, it is the logbook that will indicate how much time was on the unit when it was installed on the aircraft. Although it’s important to keep a record of each time a component was replaced on the aircraft, only the time-sensitive components need to be tracked. Simple math then determines how much time we have left on each component.

Consider the following scenario as an example of a common problem with the aircraft record: An aircraft is undergoing a Pre-purchase Inspection to determine if the aircraft meets the criteria of airworthy.

In going over the time-controlled items, the buyer discovers a part had been changed on the aircraft. Since this part is a time-controlled item, they want to see the paperwork stipulating how much time was on the unit when it was changed. The seller points them to the maintenance tracking program. They think this satisfies the requirement. But, is this sufficient?

Absolutely not! Don’t make the mistake of thinking that just because you recorded the time/cycles on the unit in your Maintenance Tracking Program, you can prove the total time on the component. The FAA has gone on record that Maintenance Tracking is only a reference and cannot be used to prove any event. The easiest way to prove the time on any time-sensitive component is to keep the original 8130 that was received with the unit … and keep it in the logbook.

Without the 8130, or another way to verify the time on the unit when installed, the buyer will usually insist that the part be changed before buying the aircraft.

4. The aircraft’s current Inspection Status.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(iv) requires the record to contain a current inspection status. Whether the aircraft follows the OEM’s Recommended Maintenance Program or has its own, the time interval and type of inspections required are spelled out in the program. It’s a simple exercise to see that the aircraft is not only current with the latest inspection, but that all inspections have been complied with.

5. A list of ADs accomplished on the aircraft over its lifetime.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(v) requires the current status of all applicable ADs. Although it is required for everyone to keep a record of the ADs accomplished on the aircraft, an AD Matrix (pictured below) is not required for aircraft operated under Part 91.

However, it’s always a good idea to keep a quick reference matrix on the aircraft. This list should include all ADs potentially applicable to the aircraft and component parts, with the ADs that are not applicable denoted as such. In this way, anyone doing a check of all possible AD Notes against the aircraft have already been addressed. Should the aircraft ever be placed on a 125 or 135 Certificate, an AD Matrix will most likely be required anyway.

Download this AD Compliance Matrix

6. A comprehensive list of Form 337’s applicable to the aircraft.

FAR 91.417(a)(2)(vi) addresses the need to have a list of the current major repairs or alterations to the aircraft. This has become one of the most popular “plan B” alternatives used in any aircraft pre-buy. Since the FAA requires everyone completing a 337 on an aircraft to send a copy to the FAA in OK City, these “copies” of the 337s are almost always requested as part of the pre-buy. This does not, however, alleviate the owner’s responsibility to keep a copy of all the 337 modifications or alterations accomplished on their aircraft.

7. The status of FAR Part 91.411 and 91.413 Altimeter and Transponder checks.

FAR 91.411(a) and 91.413(a) address the aircraft’s altimeter and transponder system accordingly. The altimeter and transponders need to be checked every 24 months at a minimum. Every time these systems are checked it should be recorded in the logbook with a Return to Service entry.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Whether you’re a Pre-buy “expert” or just one of the many thousands of aircraft maintenance professionals working to keep business aviation flying; we should all know what’s required to be in an aircraft logbook.

As an aircraft maintenance professional, it’s your job to understand what is required to be included in an aircraft logbook, and how this information can be properly organized.

Knowing this information should come with the territory. It’s that simple.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Related Posts

The Importance of Aircraft Maintenance Records- Part 1

Investing in Excellence

Blockchain in Business Aviation